One of the great mysteries of humanity’s history is how we made the transition from an isolated, emergent species to attain today’s globally dominant civilization. Scientists tell us that the story began as early as 7 million years ago in Eastern Africa. Fossils found in the Awash Valley give evidence of our early precursors. Archaeological findings suggest that some of these precursors began to fabricate and use rudimentary stone tools between 6 million and 2 million years ago. Learning to control fire followed about 1 million years ago. By 70,000 years ago homonins had migrated out of Africa and begun to apply more complex technology evidenced in hafted spears, for which a sharpened stone point was attached to the wooden shaft.

The fossil record indicates that our own species, Homo sapiens, evolved during this progression and became the sole survivor among several homonin species. The evolution included a remarkable growth in brain size as well as emergence of social behavior and technological prowess. Some scientists hypothesize an interaction between physical capability and intellectual accomplishment to explain this evolution.

British archeologist Steven Mithen, for example, surmises that early uses of technology (such as hafting of spears) encouraged development of “cognitive fluidity,†an ability to abstract and combine aspects of experience from different domains such as finding shelter or observing game. The large brain of Homo sapiens was an essential adaptation that enabled this cognitive fluidity to develop, but does not by itself explain how the development came to be. Adopting and using a cultural innovation provides the stimulus for users to extract more from their brains than they might have otherwise.

Drawing on observations of ants and other animals that exhibit eusocial behavior and altruism—in which some individuals in a colony or nest limit their own reproductive potential by raising the offspring of other nest-mates or defending the group against competitors and predators—noted Harvard biologist Edward Wilson suggests that certain “preadaptations†favor the behaviors’ evolutionary development. Among the most important of these preadaptations, Wilson conjectures, is a species’ propensity for living in defensible nests. When early humans, tribal by nature, learned to use fire and establish campsites sufficiently persistent to be guarded as a refuge, they had taken a crucial step toward modern social organization.

Wilson and his colleagues Martin Nowak and Corina Tarnita assert that the advantage of a defensible nest located within reach of reliable food sources, particularly one requiring greater energy in its construction, is a crucial causative agent in the evolutionary development of eusociality, a trait that loosely applies to humans as well as ants. A next step in humans’ social evolution beyond the adoption of movable campsites would logically seem to be long-term commitment to a fixed location. The earliest evidence of such commitment arguably is found in the Chauvet Cave walls in southern France. Images painted on the cave walls here and elsewhere (for example, the El Castillo cave in Cantabria, Spain, and others Romania and Australia) are estimated by various archeologists and methods be 28,000 to 40,000 years old.

We have no convincing evidence of the creators’ motivations for any of the cave paintings, but their permanence and often difficult-to-access locations suggest these were not simply decorations of living space, but rather demonstrations of a particular significance of place, perhaps an effort to preserve human memory as recorded history. I propose that in this sense these ancient markings are humanity’s earliest known infrastructure.

University of Cambridge archaeologist Graeme Barker has presented the evidence suggesting that the domestication of various forms of plants and animals evolved in separate locations worldwide, starting around 12,000 to 14,000 years ago. For many researchers, this domestication is synonymous with “agriculture,†a technological innovation and foundation of modern civilization. An alternate model proposed by David Rindos in the 1980s proposed that domestication of locally available plants, a co-evolutionary interaction of humans and their food sources, led to intentional agriculture and consequent selection of preferred species and strains.

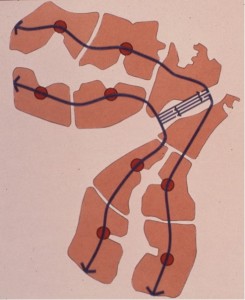

This domestication of plants has been characterized as the beginning of the Neolithic or Agricultural Revolution. Evidence, particularly from the Fertile Crescent region in the Middle East, indicates that cultivation was accompanied by construction of settlements and drainage ditches and landforms to control plant irrigation. Archeological studies by Harvard archeologist Ofer Bar-Yosef and others are currently thought to indicate that the Natufian culture in the region is the world’s oldest example of sedentary settlements and agriculture, notable particularly because the settlements may have preceded the commencement of crop cultivation.

Whether development of agriculture preceded or followed the birth of cities has long been debated. Mithan, for example, reflecting recently on the progress of human civilization, expressed a widely held view that agriculture came first, and once farming had originated, towns and cities appear to be an almost inevitable consequence. On the other hand, Jane Jacobs, an economist and unabashed urbanist, famously argued in the 1970s that labor specialization and trade first gave rise to cities, and that feeding their populations necessitated the development of agriculture. (Archaeologists notably disagree. See Smith, Michael E., Jason Ur, and Gary M. Feinman.  2014.   “Jane Jacobs’s ‘Cities-First’ Model and Archaeological Reality.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38 (4): 1525-1535.)

In either case, however, it would seem that infrastructure came first. The investment of effort in clearing fields; moving earth to adjust water flow; building fences, protective walls, and substantial shelters; maintaining paths for transportation; and the like would have contributed substantially to agricultural productivity, settlement economy, and social functioning of the residents.